Improving dementia support in Black communities

Tags

DementiaInterviews

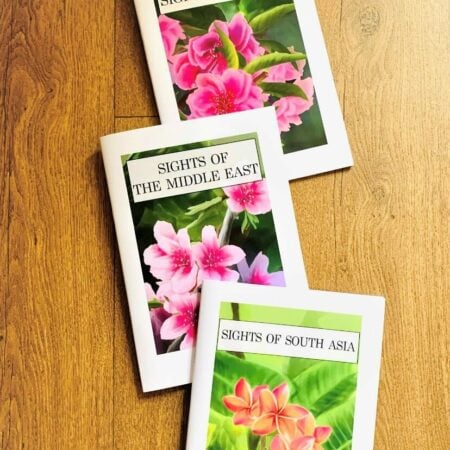

After discovering a lack of dementia resources for people of African or Caribbean heritage, Feyi Raimi-Abraham started The Black Dementia Company in 2020. Feyi is now leading the way with specialist reminiscence products, and driving important conversations within health and social care – we spoke to her to find out more about her work, and the importance of culture and roots within the dementia journey.

Could you tell us a little about your background and The Black Dementia Company?

I like to describe The Black Dementia Company as a service, because it’s more than just creating products. The mission is to improve the wellbeing of people living with dementia, but especially people who are familiar with African or Caribbean heritage.

They don’t have to have been born in those spaces – they could have been born here, or in the US or Europe or indeed anywhere else. But if they are innately familiar with African or Caribbean cultures, then we can provide something that they might find useful as they go through their dementia journey.

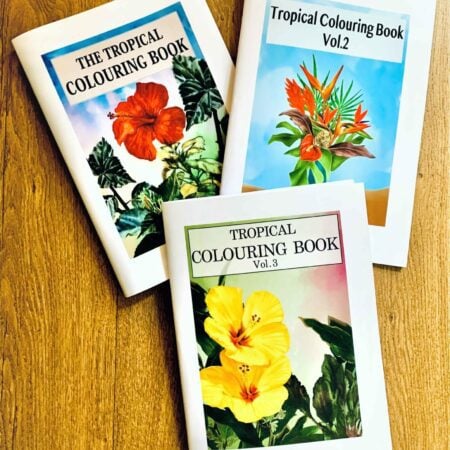

I am my mother’s carer, and she’s from Trinidad and Tobago. She’s a retired Physiotherapist, and went to University in Canada, but has also lived in different parts of the world. In her heyday she was very creative, and used to sew and also do a lot of sketching. So her interests and experiences are quite wide. But one thing I found was that since starting her dementia journey, when she was presented with things that were innately familiar to her Caribbean heritage, you could see a different level of joy.

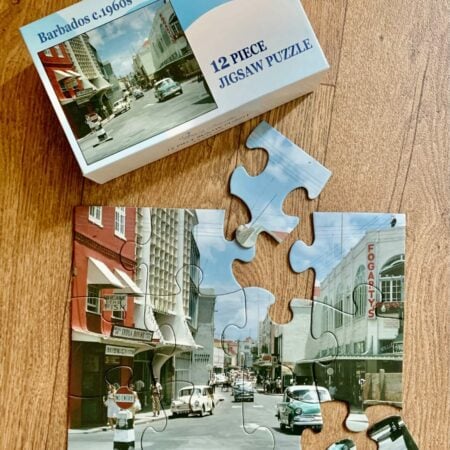

So last year, during the first lockdown, I thought I’d look to see what else was available for somebody like her, and I found that there was nothing out there. There’s a lot in terms of reminiscence – puzzles and games and everything else, but nothing directly linked to people of African and Caribbean heritage. And I thought I’ll try and provide that service with The Black Dementia Company.

Were you surprised at the lack of resources available for those from an African or Caribbean heritage, living with dementia?

I was mostly surprised that nobody else had thought about doing it, and sadly, not so surprised that the mainstream organisations didn’t have those resources available.

My view has been not to dwell on apportioning blame but to say okay, we’re here now and willing to work with others to foster understanding and also ensure that there are dementia products and services available for all communities. And that’s why I describe the company as a service, because I’m very much interested in public engagement, supporting and helping organisations and researchers as well. Let’s talk, and let’s see how we can service this very important part of society.

I think the very important thing, especially for African and Caribbean communities, is that one must talk about dementia, you can’t just keep it to yourself and hope that you will cope through it.

Feyi Raimi-Abraham

What’s been your experience of being your mother’s primary carer, especially over the last 12 months?

I have been her primary carer even before her dementia diagnosis, I just naturally fell into that role of being the one to take care of her chores, shopping and communicating with doctors and that sort of thing.

From speaking to others I think my experience is similar to a lot of people. It’s a shared experience, in the sense that you just flow with it, you do what you have to do. It can be challenging, but at the end of the day, the wellbeing of your loved one is at the forefront of everything you do. And even though sometimes you can be taken aback – maybe yesterday, you were able to engage in a game of Scrabble with your loved one. And today, they just can’t focus. At the same time, it’s about trying to find time for oneself in the midst of all that.

I think if there’s any sort of message that I try to give is that, it’s okay, to feel sad, it’s okay to feel frustrated, dementia is a terrible condition. As long as those frustrations aren’t translated to the care that one gives – it’s important to validate your feelings, but then remember that you’ve got somebody that is relying on you to keep them safe.

And for anyone who’s not quite there yet, but is seeing signs that they might have to fall into that role of carer, remember there are so many different services available in terms of information. And I think the very important thing, especially for African and Caribbean communities, is that one must talk about it, you can’t just keep it to yourself and hope that you will cope through it.

I know it’s not easy, especially within our communities for many different reasons. But it’s important to know that it’s okay to ask for help.

You mentioned working with organisations that support those living with dementia, how have you found those conversations?

Shortly after launching, I was featured on BBC CEO secrets last year. And after that I was contacted by a University and was invited to give a talk to a whole group of researchers. I’ve been contacted by memory services too, so I’ve given quite a few talks. I’m just trying to shed light on some aspects of culture that they may not be aware of, or they may see but not understand, and try to help them find ways to reach out and make sure that they are offering services to as many diverse groups as they can.

Do you think there needs to be a better understanding of the experience of dementia for those from an African or Caribbean heritage, particularly for those living in residential care?

One person actually got in touch to share a story about their mum, who was from the Caribbean and living in a home. Whenever there were communal activities in the home it was always those wartime Vera Lynn songs that they would tend to play in the home. But when this person was able to play music that resonated with their mum – Caribbean music, the difference in their mother’s demeanour was clear. So there is that gap, and with the projects that we have at the moment, it’s all about trying to help with starting the conversation.

Our puzzles and colouring books are not there as substitutes for care, it’s about trying to use the products to encourage the person to engage in conversation, especially about what is familiar to them.

The other thing I’ve said in a few of my talks is that it’s very important to understand that African and Caribbean culture is made up of so many different subcultures. So, within those wider spaces, you have people of Middle Eastern descent, people of Asian, South Asian, Chinese descent, people of European descent.

So it’s about trying to help people understand that it’s wider than just colour. And also help them understand ways of trying to engage. So, hopefully, as time goes on, people can inform themselves, because obviously it’s not realistic for everybody from a certain culture to only be cared for by a carer who shares that heritage. But if carers in residential homes, for example, have something that they can use as a seed, to start conversations such as ‘oh, you know, this looks like a harbour in St. Lucia’, or ‘does this place look familiar to you?’ then we’re winning.

The Alzheimer Society has highlighted BAME communities often face delays in dementia diagnosis and barriers accessing services. What do you think needs to be done to ensure we’re protecting the wellbeing of these communities at every stage of the dementia journey?

One thing I say to people is that across all communities, there is an element of stigma attached to dementia, and that could be because people don’t understand the condition. And, particularly within African and Caribbean communities there could be so many reasons for people not coming forward.

Some that have come to light are that people just want to just get on with what they’re doing, and not feel that they are a burden to others. People being embarrassed, and people not understanding the condition, or thinking it’s just part of old age.

However people also often feel that there’s no service for them. One thing I’ve said in my talks is that professionals have to find a way to reach out to these communities. We’re storytellers, innately. I’m sure it’s the same in other cultures, but I have lived experience with African and Caribbean culture, and narrative goes a long way. The shorter the narrative, the more suspicious people will be. If you just say to people ‘come and join this dementia group’ people are going to ask why. So it’s about reframing the manner of engagement.

It’s about trying to help people understand that it’s wider than just colour. And also help them understand ways of trying to engage.

Feyi Raimi-Abraham

It’s also important not to firefight – don’t wait for there to be a problem, or for the statistics around these communities not engaging with services to become high. So it’s more about looking for the reasons why they are not engaging and explaining why you are so interested in talking to the community, and why it is so important for people to know more about dementia. As opposed to just saying, well, there’s a memory service here, if you experience any issues come to us – people aren’t going to come naturally like that.

And, in terms of conducting research within these communities – outputs are enriched by the inputs. I’ve seen other research papers talking about black and ethnic minorities not engaging, but that’s a lazy thing to say. When people say, well, they’re not interested because they look after themselves and their family members, it’s not about that. It’s more about saying, Do they fully understand your motive in wanting them to be part of this research or service?

Is there a final message you’d like to share about the work of The Black Dementia Company, or about the dementia experience?

At the end of the day, our focus is the end user – the person living with dementia. And that’s what I would like people to be aware of.

We sometimes get comments about, you know, the puzzles are nice, but they’re not very colourful and things like that, but it’s not about making things pretty for anybody else. It’s about thinking, how can these products be approachable to whoever it is that they’re going to be placed in front of, and to remember that it’s part of a conversation, it’s not just leaving them with it, you have to have the time to engage with them as they do.

And with that, people should be willing, if they can, to have conversations about dementia, find out more, and inform themselves about the condition because it’s true that you will understand better. People shouldn’t be afraid to talk. And there are so many services out there where people can ask their questions and get answers that can help the conversation.

The Black Dementia Company provides products and services designed to improve the lives of people living with dementia from the global African and Caribbean community.

To keep up to date with The Black Dementia Company follow @blackdementiaco on Twitter to take a look at their website below.

Read our latest interviews

Browse our latest interviews, and research on elderly living, from leading national experts.